Results & Impact

As a non-profit organisation, we employ 7 full-time staff to carry out 100 consultations with educational institutions every year in order to win them over as programme providers. We grow by 15%each year andtrain 250 educational professionals in a total of 15 courses to become Award Leaders. This results in a pool of 700 trained volunteers.

The trained Award Leaders then offer the Award to a target group of 50,000 young people between the ages of 14 and 24 at currently 160 educational institutions.

60% of the educational institutions are public schools, 30% private and 10% universities, companies and associations.

Last year, 3,000 young people actively worked on their Award at 160 educational institutions in Germany. 2/3 of the participants come from private educational institutions and 1/3 from public educational institutions. 50% of the participants are between 14 and 17 years old. There are no differences between the genders.

In 2023, young people invested 40,000 hours in volunteering, playing sport and discovering new talents. A further 3,000hours went into expedition preparation, as well as almost 1,000 days on expeditions.

713 awards were verified and presented by us in Germany last year. We invest €143 per participant.

Worldwide, there are more than 1 million active participants and 180,000 adults who accompany this process as mentors.

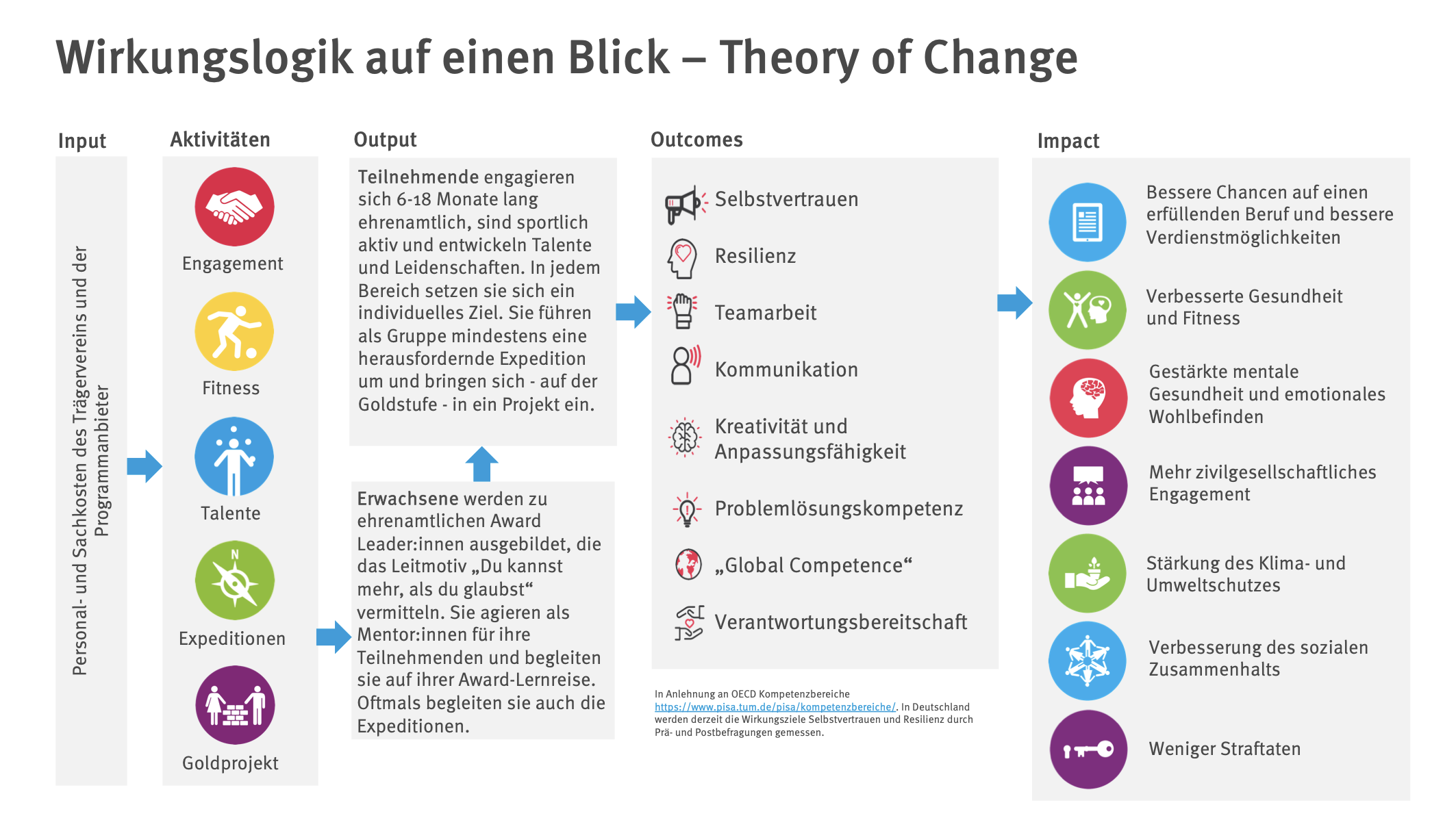

Based on the competences from our impact logic (see above), studies on the effectiveness of the Award have been conducted worldwide. This has yielded significant results in the following areas (the sources are listed in the menu under Literature):

Self-confidence & agency: defined as self-confidence, self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-belief, ability to shape one’s own life and the world around one (2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 27, 28, 30, 31)

Resilience and determination: defined as self-discipline, self-management, self-motivation, concentration, determination, perseverance, self-control (2, 3, 4, 6, 19, 11, 17, 24, 28, 26, 27, 29, 30)

Teamwork: relationships & leadership defined as motivating others, valuing and contributing to teamwork, negotiating, building positive relationships, interpreting others, managing conflict, developing empathy (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 17, 20, 21, 23, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30) and managing feelings defined as scrutiny, self-awareness, reflection, self-regulation, self-acceptance (3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 19, 27)

Communication: defined as explaining, expressing, presenting, listening, asking questions, using different types of communication (9, 21, 30)

Creativity: defined as imagining alternative approaches, applying what has been learnt in new contexts, enterprise, innovation, openness to new ideas (9, 21, 26, 29)

Planning and problem solving: defined as navigating resources; organising, setting and achieving goals; decision making, researching, analysing, critical thinking, questioning and challenging, assessing risks, reliability (2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30)

Global competences: defined as intercultural competence and the ability to work in different cultural environments (with different age groups, abilities, religions, languages, etc.) and adaptability to changing circumstances and the ability to recognise and respond to new contexts (21, 26, 30)

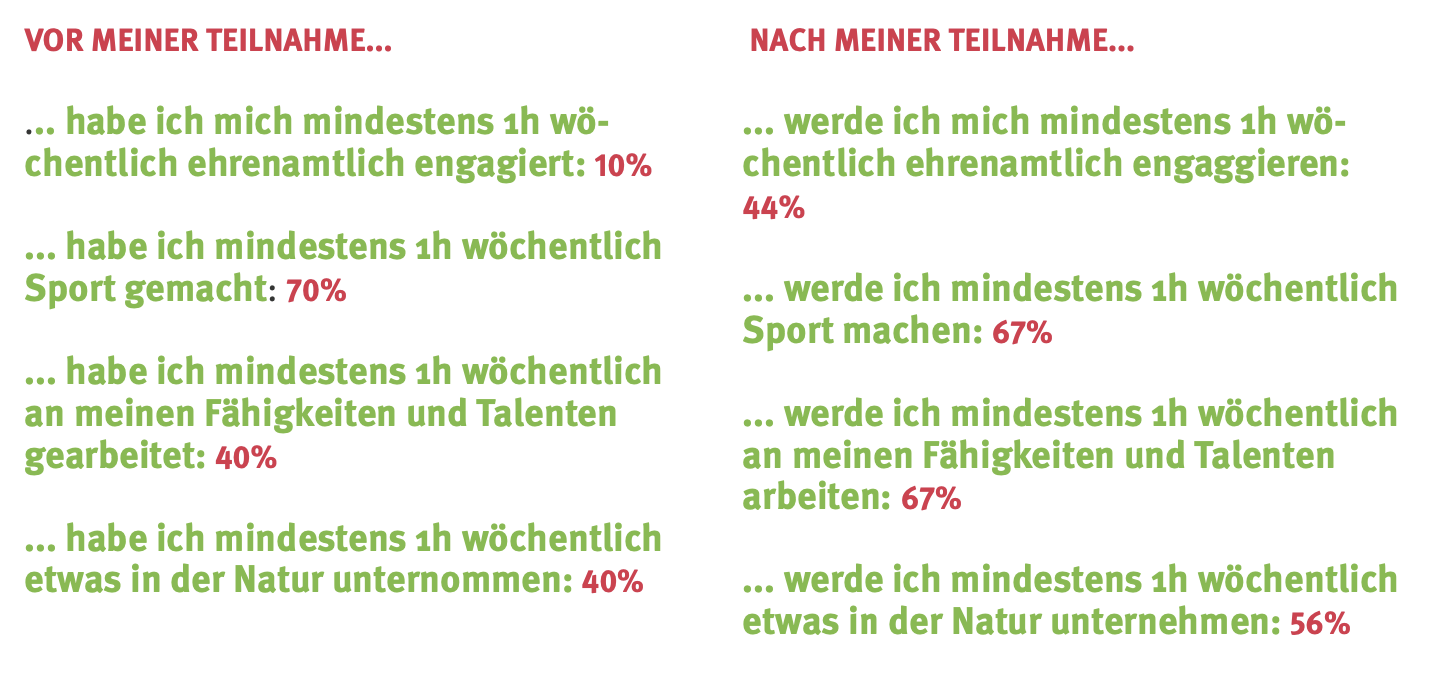

The acquisition of these skills, the changed perspectives (‘I can do more than I thought’) and the new attitudes (‘I can achieve a lot of things that are important to me if I just set my mind to it’) lead to changes in behaviour: Participants are increasingly active in sports, they acquire and strengthen new skills on their own responsibility and/or devote themselves to newly discovered passions (national figures from 2023):

Participants’ changed behaviour leads to new life situations: Participants are socially active, physically fit and mentally strong as a result of their activities. They have better chances of getting an education and a fulfilling job. They are integrated into a social network and are less likely to commit offences. They contribute to social cohesion and to solving social challenges.

Better opportunities for a fulfilling job and better earning potential

- 91% of participants reported that they had improved their skills in teamwork (91%), communication (75%) and problem solving (59%) (UK study, 2014)

- Young people in England, Wales, New Zealand and Scotland report that the skills gained through the Award help them find a job (Dubberley, 2010; Milliken, 2016)

- Employers value the Award as it demonstrates leadership, initiative and social responsibility (Yoganathan, 2009).

- Over a quarter of UK organisations favour candidates with the Award for key skills such as teamwork, communication and problem solving (CIPD, 2015).

- 93% of respondents would be more likely to hire candidates with extra-curricular achievements such as the Award (The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award UK, 2017).

- Universities in Ontario recommend the Award to demonstrate commitment and personal achievement (Lico, 2008).

Improved health and fitness

- The Award has a positive impact on health through physical activity, both psychologically (making new friends, stress reduction) and physically (improved stamina and fitness) (Award UK, 2015).

- A global survey (2018) showed that young people around the world are participating more in sport and exercise as a result of the Award (The Foundation, 2019).

- In a study in Fiji, 100% of Award participants surveyed agreed that the Award promotes physical health (Singh, 2018).

Strengthened mental health and emotional well-being

- A survey in the UK showed that 97 % of participants were happier as a result of volunteering. 77% felt more confident as a result and 46% reported improved self-esteem (The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award, UK, 2016).

- A study in Fiji found that all 22 participants surveyed believed that the award promoted mental well-being (Singh, 2018).

- A study in the UK showed significant improvements in self-esteem after completing an expedition (Gibbs and Bunyan, 1997).

- The Award contributes to the development of life, social and leadership skills (Naylor et al., 2017).

More civic engagement

- Research in the UK showed that 62% of respondents felt they had made a positive contribution to the community through the Award (Campbell et al., 2009).

- 82% of participants reported that the Award motivated them to volunteer and 61% of Gold Award holders remained involved in their community (Campbell et al., 2009).

- Smith and Isles (2004) found that participation in the Award promotes civic education and understanding of citizenship.

- In Ghana, Alice Agyiri and Esther Chinebuah founded the Youth Empowerment Service (YES) during their Bronze Award to help children and families (Agyiri & Chinebuah, 2010).

Strengthening climate and environmental protection

- A study in Canada found that participants developed a greater understanding of environmental issues as a result of the expedition (McKinsey & Company, 2010).

- 75% of Gold Award holders considered the expedition to be valuable for their personal development (The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award, 2007

- Cranfield (2005) emphasised that the expedition section of the Award promotes environmental awareness and teamwork.

- Singh’s study (2018) showed that the Award leads to greater environmental awareness.

Improving social cohesion

- 41 participants from five countries (UK, Israel, Netherlands, Ireland, Finland) reported positive impacts on personal growth and social skills (The Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award Foundation, 2015).

- The Award provides positive experiences and achievements for children with visual impairment (Wrench, 2011).

- The Award promotes personal growth and global citizenship (Milliken, 2016).

- The Award raises awareness of the needs of others and contributes to the fight against poverty and inequality (Flanagan, 2001).

- The Award in Fiji promotes social engagement and inclusion (Singh, 2018)

Fewer criminal offences

- Robathan (2001) reports benefits for young offenders, including increased self-esteem.

- The Award reduces offenders’ risk of reoffending and promotes social skills (Dubberley et al., 2011; Dubberly & Parry, 2009/2010).

- The Award helps young offenders to avoid conflict and cope with daily life in prison (Dubberley, 2010).

- An evaluation in South Africa showed positive behavioural changes and increased self-esteem among participants (Umhlaba Development Services, 2003).

- The Youth Resiliency Project in Canada showed that the Award promotes positive behavioural change (Yembilah, 2019).

- The Award contributes to reducing violence and conflict in Fiji (Singh, 2018)

The societal value of the programme is the positive impact that the programme creates for and through its stakeholders, which can be expressed in monetary terms.

Since 2017, the Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award Foundation research team has been working with PricewaterhouseCoopers UK (PwC) to understand the impact of the programme at a societal level. Together, a robust methodology was developed to measure this. The study estimates that the Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award created a global social value of $970 million (€895 million) in more than 120 countries and territories in 2022.

And with a projected global social value of $2,513 million (€2,320 million) to be generated by the continued habits of these Award alumni, this demonstrates the significant impact the programme can have long after participation has ended.

World Bank: Measuring Social Value 2024 Social Value Report 2023 Social Impact Report 2020Social Impact Report 2019

Here you can find our national impact reports.

Here you can find figures on the global impact of the award.

The Award in numbers Annual Report 2023