Societal challenges

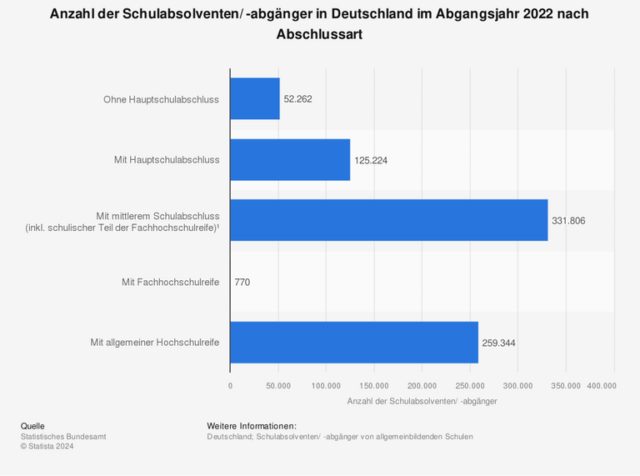

Many young people in Germany are not realising their full potential. A lack of support in the family, nursery and school leads to behavioural problems, resignation, guilt and mental illness. They leave school with little or no qualifications and no prospects for the future.

By ratifying the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1992, Germany committed itself to ensuring the best possible development of young people. This right is being violated. Furthermore, Germany does not sufficiently fulfil the UN Sustainable Development Goals, in particular No. 3 (health and well-being), No. 4 (quality education), No. 8 (decent work and economic growth) and No. 13 (climate action).

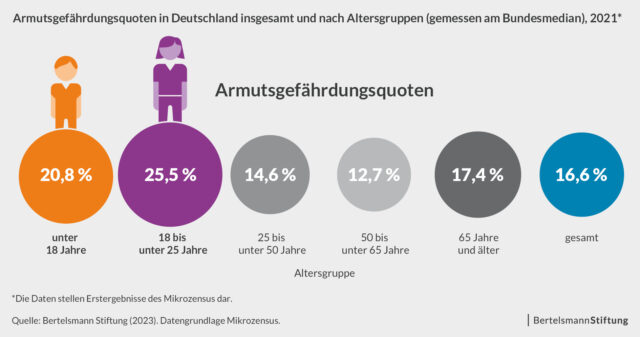

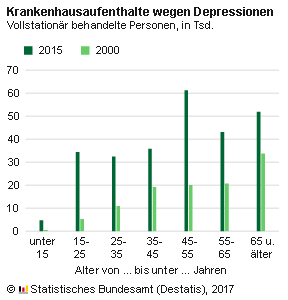

Up to 20% of children and adolescents in Germany suffer from mental disorders such as anxiety disorders, hyperkinetic syndrome, learning disorders, depression, addictions and eating disorders. These untreated problems often continue into adulthood, where the prevalence rises to 25%, making mental disorders one of the biggest challenges in the health sector. The most important risk factor for mental illness in young people is socio-economic status (SES): children from socially deprived families are more at risk. (Dts. Centre for Mental Health 2024)

The results of the meta-study by Färber & Rosendahl (2018) show a significant correlation between resilience and mental health. Resilience was defined with the following competences, among others: self-confidence, perseverance, adaptability, tolerance, flexible view of oneself and one’s own life path.

The prevalence of overweight in children and adolescents is 15.4% and for obesity 5.9%. Children and adolescents with a low SES are more frequently affected than those with a high SES (RKI 2018). Overweight and obese children are more likely to have risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, such as high blood pressure, lipometabolic disorders and glucose metabolism disorders (Friedemann 2012). A high BMI in childhood and adolescence is associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in adulthood (Llewellyn 2016). Being overweight also leads to a lower quality of life and a higher risk of bullying (Puhl 2013).

Only 22.4% of girls and 29.4% of boys between the ages of 3 and 17 are physically active for at least 60 minutes a day and therefore fulfil the WHO’s physical activity recommendation (RKI 2018). Low physical activity ismore common among female adolescents and children from families with low SES. In Germany, insufficient physical activity contributes significantly to deaths from coronary heart disease (12.3 %), stroke (7.6 %), diabetes mellitus (3.1 %), colorectal cancer (3.4 %) and breast cancer (1.8 %) (Global Burden of Disease Study 2016). There is also a link between school sport, leisure activity and a lower risk of mental illness (White 2017). Promoting physical activity in childhood and adolescence can prevent obesity, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, promote healthy development, better cognitive and academic performance and increased physical activity behaviour in adulthood (Lee 2013; Rauner 2015; Britto 2017; Ng 2017).

Access to high-quality education and thus educational success in Germany continues to be dependent on social background.

This is reflected in a low level of education among parents, unemployment among parents and a household at risk of poverty. The high dependency on social background is also evident in the longer term in the qualifications achieved: for example, 79% of children from families with a high socio-economic status achieve university entrance qualifications among 20-year-olds, but only 31% of children from families with a low socio-economic status.

In families with a migrant background in particular, the probability of having at least one of the risk factors is 48% (16% without a migrant background). In addition, people with a migrant background who moved to Germany at the age of 19 or later are much more likely to have no vocational qualification or higher education entrance qualification (32%) than people without a migrant background (8%).

The urban-rural divide is also of great significance: In large cities, the proportion of 30 to 35-year-olds with a university degree is significantly higher (49%) than, for example, in the predominantly eastern German districts and independent cities (17%). (Author: Education Reporting Group, Education in Germany 2022)

The number of unemployed people in Germany last year was 2.6 million (2023). This is a dynamic figure: 2.2 million people registered as newly unemployed in 2023 and 1.7 million people took up new employment. This coincides with a shortage of skilled labour in over 200 sectors in Germany. However, 50% of the unemployed are looking for occupations on a helper basis and have no qualification as a skilled worker, whereas 80% of the registered jobs are aimed at skilled workers.

At 20.8%, the unemployment rate for people who have not completed vocational training (a lack of training usually goes hand in hand with the search for a helper’s job) is more than six times higher than that of people with a vocational or academic qualification (3.2% and 2.5% respectively). (Statistics from the Federal Employment Agency 2024)

According to the OECD study ‘Education at a Glance’ from 2023, the proportion of 25 to 34-year-olds without a secondary school leaving certificate or vocational training in Germany rose from 13% to 16% (234,700 young adults) between 2015 and 2022. The number of 18 to 24-year-olds who are neither in employment nor in training is 8.6% (527,000 young adults). The number of people who attended secondary school and subsequently obtained a vocational qualification fell from 51% (2015) to 38% (2022) over the same period.

With regard to the employment rate and gender equality, a lever can also be recognised here: 80.2% of men in Germany work, as do 73% of women. Of these, however, 67% of mothers work part-time and only 9% of men. 40% of women stated that they had to make this decision for personal and family reasons. (Federal Statistical Office 2023)

Inadequate daycare and nursery provision, expensive care places for relatives, combined with a shortage of nursery teachers and carers, make it difficult for many families to return to full-time employment.

Human activity causes more carbon dioxide (CO2) to enter the atmosphere, which intensifies the natural greenhouse effect. This causes the earth’s surface to heat up even more. This warming has many serious consequences, including droughts, heat waves, extreme weather events, warming of the oceans, rising sea levels and species extinction. To stop this development, we must become climate-neutral so that the earth does not heat up by more than 1.5 degrees. To achieve this, CO2 emissions must be avoided and reduced.

In order for politicians to realise this, we need citizens who support these decisions and consider nature to be worth protecting. The experience of nature in childhood and adolescence is absolutely formative for nature-related behaviour as an adult (BPB 2022 & Gebhardt 2009). In addition, positive experiences of nature in childhood and adolescence promote the willingness to behave in a nature-friendly way later on, to accept restrictions to protect nature and/or to get involved in nature conservation (Rosa Collado 2019).

The influence of social background is also evident here: studies conducted primarily in the USA show that children and young people from educationally disadvantaged and low-income families are at a disadvantage when it comes to access to nature (BPB 2022).